Blog: DFID 2.0…? Some wild-ish speculation on UK development cooperation, 2025-2030

DSA member Andy Sumner of King’s College London looks into his crystal ball and ask what a change of government in the UK might mean for UK development cooperation and policy. This first part of the blog asks what has changed since 1997 (when DFID was established) and what a new government would inherit.

The second blog then turns to the questions of whether a new DFID will rise from the ashes; whether aid spending will return to 0.7 of gross national income and what a change of government might mean for the focus of UK development co-operation and policy.

The UK will have a general election by January 2025, most likely in autumn 2024, perhaps close to the US presidential election.

The polls suggest a potential wipe-out for the ruling Conservative party, who have been in government since 2010. A majority in the House of Commons looks likely for the Labour Party, though it can’t be taken for granted and may be much smaller than the polls suggest. Although some kind of Labour majority seems the most likely outcome, it is important not to dismiss the potential for a coalition (e.g. Labour-Liberal Democrat) government if there isn’t a majority for any party.

If there is a new government, things couldn’t look much more different to 1997 when Labour was elected, and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) was launched.

Domestically, the incoming government faces a country falling to bits, in some cases literally (crumbling concrete in schools, hospitals, universities, airports, and other public buildings); a Brexit process only just about to be fully implemented with knock-on impacts on food prices coming soon.

Crucially, the fiscal situation looks bleak but is little discussed – leading institutes argue no parties are being open with the public about what is to come.

In the UK context the main discussion of UK development policy amid all of these headwinds has been around the current government’s new ‘white paper’, which seeks to set UK development policy to 2030 and tried to be cross-party. That said, it could have a very short shelf life as presumably any incoming government, especially one with a reasonable majority, would want to set out its own brand or agenda.

So, what has changed since 1997 when DFID was established by the new Labour government and what will the incoming government inherit in terms of UK development policy?

What’s changed since 1997?

In 1997, the incoming government faced a benign context, both fiscally and globally. The global context for development cooperation post-pandemic is the exact opposite.

Globally, there is the new geopolitics dynamics of conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East. The rise of populist nationalism, rolling back of democracy in some countries as well as declining public support for democracy in some regions. Possibly a second Trump presidency. Weak support for multilateralism. And the window for smoother transitions to adapt to climate change that is already ‘baked in’ is narrowing.

In short, the post-pandemic world presents a challenging environment for development cooperation. Most urgently, post-pandemic debt servicing is offsetting a significant portion of Official Development Assistance (ODA), with the ratio of debt servicing to ODA reaching a third or more in some of the world’s poorest countries, judging by a quick look at World Bank data.

The real debt crisis isn’t only the potential for financial crises though that is there, but the silent crisis of debt repayments and austerity measures squeezing out social and productive expenditures.

At the same time economic growth in many developing countries is weak and economic development stalled or proceeding at snail’s pace, with the real possibility of the end of the manufacturing pathway to development.

Not surprisingly, the world is unlikely to meet the headline, poverty-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. In fact, a need to extend the SDG timeline, presumably to 2040, looks inevitable and – perhaps – politically plausible. The alternative would be to agree a new agenda, perhaps more in keeping with the current context and policy narratives on poly-crises or perma-crises and multiple human insecurities – but that would require a lot of multilateral energy and discussion to be had in a relatively short space of time to build a new political consensus in five or so years.

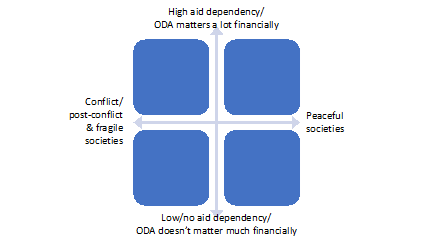

What has really changed though, in the Global South over the last 30-40 years is the emergence of a dual polarisation, first between countries where aid is essential for the government to function and deliver basic services and many countries where traditional aid just doesn’t matter anymore, due to expanding domestic resources. Then there is a second, off-cited polarisation between conflict/post-conflict and peaceful countries.

That makes four contexts (see figure below):

- countries where ODA does matter a lot and are in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does matter a lot and are not in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does not really matter and are in conflict/post-conflict situations.

- countries where ODA does not really matter and are not in conflict/post-conflict situations.

Traditional ODA caters for 2 of the 4 places – the ODA matters ones – but that is home to half of global extreme poverty. So, what about the places where ODA doesn’t really matter and the other half of global extreme poverty? There is much that development cooperation can do and does do in places where ODA matters less, and it is not necessarily about spending large sums of money. Potential avenues are policy coherence (e.g. trade policies or supporting new global tax rules), or supporting more open policy processes (though this can look like political meddling); or widening the evidence base in policy making, bringing evidence from other contexts and supporting national think tanks, technical assistance (though note the loss of UK expertise in FCDO that was reported by the Independent Commission on Aid Impact) and co-financing global and regional public goods.

Figure 1. Four contexts for development cooperation

Second, what will the new government inherit?

The UK’s development policy has been marked by large cuts in the ODA budget, causing ‘real pain’ (according to the World Bank’s number 2) and resulting in one-third of what is counted by the UK as ODA being spent within the UK, not in developing countries.

The aftermath of Brexit and the withdrawal from EU development policy, along with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) ‘merger’ (actually a takeover) of DFID in 2020 (apparently without any planning ahead of time), have, according to the Independent Commission on Aid Impact (ICAI), led to a dominant foreign policy culture, and a loss of DFID expertise, a decline in transparency, less focus on evidence, a reduced culture of internal challenge, and the risk of a large-scale loss of institutional memory.

In short, that is the legacy that a new government would inherit. Maybe the White Paper tries to tidy it up a bit, but it’s a lot to turn around. The White Paper does re-establish poverty reduction as a key aim though the White Paper is not as ambitious overall as it might have been.

In the second part of the blog Andy will discuss whether a new DFID will rise from the ashes, whether aid spending could return to 0.7% of GNI and what a change of government might mean for the policy focus of UK development co-operation.

This blog first appeared on the From Poverty to Power website.