Cambridge submit evidence on aid contracting

In November 2024, the International Development Committee launched an inquiry into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) approach to achieving Value for Money in its aid programmes.

The University of Cambridge submitted evidence in response to these enquiries. Their full evidence into development contractors and consultants is below. The university also contributed a proposal in response to call for potential topics of enquiry that the International Development Committee examine the ODA-funded consultant and contractor (supplier) market, as they identified a number of trends that have emerged since the last time this issue was examined (International Development Committee 2017; ICAI 2017, 2018).

Development contractors and consultants research

This contribution focuses on the way Value for Money is achieved through the design, procurement and management of private sector suppliers for ODA-funded projects within the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. For the purposes of this contribution, we understand Value for Money (VFM) as effectiveness, efficiency, economy and equity (the ‘four Es’), following current FCDO policy. Questions of Value for Money in programme delivery are closely bound to procurement concerns over balancing cost with quality.

We start by recognising that these debates are taking place in a period of considerable change in global as well as UK development thinking and approaches, including in relation to development finance and development diplomacy. Business as usual is unlikely; but coherence and effectiveness will continue to be vital principles.

Our contribution is based on a detailed study of the interaction between DFID/FCDO and its for-profit supplier market, as part of a three-and-a-half year project funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (‘Development consultants and contractors: for-profit companies in the changing world of Aidland’, 2021-25).[1] We are happy to supply details of our methodology, evidence base, and wider analysis on request.

1) Key findings

The absolute ODA volume awarded as contracts to suppliers increased dramatically from 2012-2016 as the ODA budget expanded without parallel expansion in DFID/FCDO staff. From 2016 onwards, citing concerns to prevent “excessive profiteering” (ICAI, 2017: ii), and in an effort to secure Value for Money through an emphasis on the bottom-line, DFID/FCDO successfully exerted pressure on the margins and commercial models of the suppliers. Suppliers identified a broader ‘adversarial shift’ (reported in many interviews), embodied in capping fee rates, powers to recover profits, a transfer of performance risk to suppliers, increased compliance costs and increased cash flow capabilities in pre-qualification and practice.

The shift to a more adversarial posture towards their suppliers combined with inconsistent pipelines resulted in changes in business mode, comprising:

- A loss of internal technical capability as prime contractors increasingly emphasised management, legal and compliance capabilities over technical capabilities – the latter were increasingly sub-contracted (post 2016) and then (interviews suggest) increasingly reduced post 2020, as the budgets became tighter;

- A consolidation of firms through mergers and acquisitions, as larger firms (including non-specialist engineering and professional service firms) have acquired smaller niche firms to build volume and market share (Taylor & Gilbert 2024), and as larger firms seek injections of capital;[2]

- A sharp bifurcation in the market between prime contractors and smaller sub-contractors firms, followed by a loss of smaller firms as they went out of business or were acquired

- A re-balancing of the internal bidding process to favour the commercial element/personnel/process over the technical element/personnel/process.

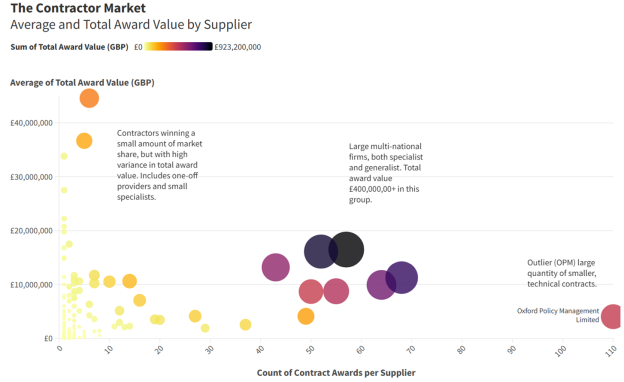

Figure 1 – Based on original research, a graph of average contract value, count of individual contract awards won and total award value secured by each contractor shows market bifurcation, with small and medium firms on the left-hand side, and only a smaller group of large multi-nationals able to ‘prime’, and dominating market share. These firms include: Mott Macdonald, Palladium, DAI, PwC, Crown Agents, Tetra Tech, Adam Smith International and DT Global. Data based on analysis conducted by ESRC team.

Figure 1 reflects the (deepening) process of bifurcation in the supplier market, between large firms winning more and larger (£400k-£900k) contracts, while the remaining smaller firms win fewer and smaller contracts. Outliers include OPM, which receives unusually high numbers of lower value contracts, seemingly as a result of specialization in Monitoring & Evaluation; as well as specialist providers like IMA World Health, which has won very few, extremely large contracts.

Our recommendations are a response to the downgrading of technical capability within the main suppliers, and the parallel loss of technical capability within FCDO, which weakens FCDO’s ability to hold suppliers to account (ICAI, 2023). FCDO contracting is frequently complex, adaptive and influenced by political priorities. In contract terms, FCDO programming is therefore often unobservable, insofar as it is difficult or at least very expensive to hold to account, because good quality work relies on socially and politically sensitive practice; and it is incomplete, insofar as the contract cannot be fully stated in advance, leaving open difficulty in enforcement and accountability. Despite much work in the sector on evaluation and results-based management, the measurement of development outcomes – especially resulting from specific contracts – remains complex and expensive.

We found that suppliers have become increasingly responsible for both management and technical specification of work. Responsibility for designing and managing all or some of the contracted work was increasingly delegated to suppliers (particularly from 2019 onwards), alongside a growing reliance on contracting through funds and facilities. In our engagements with delivery partners in-country, we found that these trends are undermining the localisation agenda.

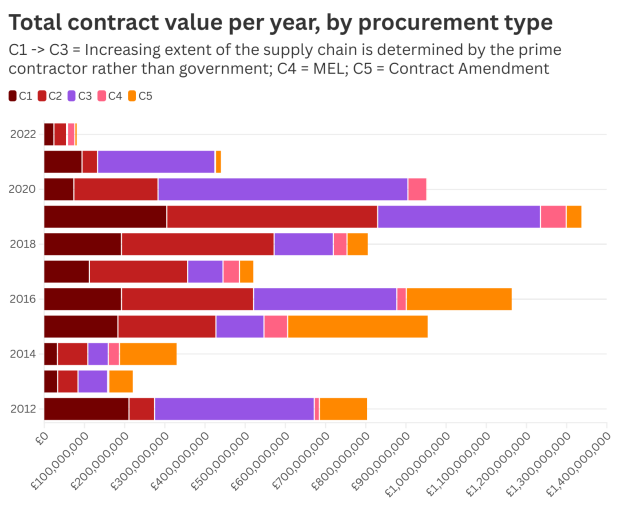

Figure 2 – Total contract value per year awarded to UK private sector contractors, coded by the ‘type’ of procurement. C1 to C3 is a sliding scale of increasing control over terms of procurement responsibility, where C1 = No significant delegated procurement for the winner of the prime contract; C2 = Delegated procurement for specific and defined activities; and C3 = Broad delegated procurement responsibility for a fund or funding facility. Of less importance here are C4 = Audit and MEL activities and C5 = Contract amendment with additional cost implications. The graph shows that C3 was used substantially in 2012 (much of this is accounted for by the Girls Education Challenge fund), 2016, and 2019 – 2021, albeit with diminishing overall contract expenditure. ‘C1’ type contracts are consistently the least used contract type.

Figure 2 suggests that since 2015, and particularly since the DFID-FCDO merger, funding windows / grant management contracts have taken up an increased share of contract awards, and contracts where DFID/FCDO maintains control over the terms of the procurement and implementation chain have decreased in prominence. This is particularly notable since 2020. Putting this together with the bifurcation of the supplier market depicted in Figure 1, we can discern a pattern of larger contracts, with less DFID/FCDO control, being awarded to fewer and larger firms. This pattern likely reflects the combined impact of a growing aid budget post-2015 and the (earlier) enshrining of the 0.7% GNI ODA target, and staffing pressures at DFID/FCDO. However, because of the impact this has had on the supplier market (see Figure 1), it will require both an increase of in-house technical capacity, and changes to procurement practices, to avoid further jeopardizing the viability of small, expert firms.

2) Recommendations

(a) Reduce delegation of intermediate management responsibilities

To improve the effectiveness of aid work, we recommend that FCDO reduce the delegation of management and technical responsibilities to intermediate contractors, retaining direct engagement as much as possible to delivery work. To do this, FCDO should decrease the size of contracts, move away from the use of Fund and Facilities as modalities, and should increase in-house technical capabilities to manage smaller contracts.

The complex, practice-based – and therefore to some extent unobservable and incomplete – nature of contracts calls for relational contracting of complex programming (see e.g. Brown et al 2016). What this means is a closer relationship between FCDO staff with delivery work, in order to ensure high quality work and hold suppliers to account; combined with ongoing third-party evaluation. Layers of management intermediaries are inimical to this kind of work. This was a recurring theme arising from our fieldwork in sub-Saharan Africa, though some form of financial oversight through an intermediary was repeatedly cited as necessary as long as dedicated budget lines for capacity development in this area were included in contracts. This recommendation is consistent with the localisation agenda and the emphasis on the use of smaller firms (a trend that appears to be underway in the US, and may well be supported in the next administration).

(b) Move to collaborative rather than adversarial contract relations

The contractual application of commercial pressure concentrating on reducing costs through the procurement process is not necessarily an effective strategy to ensure good quality development work, particularly in areas which are complex, and whose outcomes are unobservable or incomplete. FCDO should cultivate a supplier market of technically committed firms. To do this, we recommend the following:

- A return to a more active and consultative form of market management (see also ICAI, 2017), targeting not simply the major suppliers but the band of smaller and intermediate suppliers;

- A commitment to medium- to long-term thematic priorities and a pipeline of programme opportunities, to ensure the ability to commit to in-house technical capabilities;

- A removal of the cap on fee rates and instead a reliance on competition to ensure Value For Money in programming;

- Continued insistence on transparency on the margins and overheads built into contracts throughout the supply chain and retention of powers to seize excessive margins under s.19 of the Standard Terms and Conditions;

- Revisit the manner in which s.19 powers are to be used in the context of PbR contracts, which are designed to incentivize good performance – in particular, firms should not be expected to bear the penalty for poor performance, whilst having their profits seized in case of good performance

- Revisit the use of PbR contracts for more complex and opaque programmes, which are difficult to measure and where attribution is challenging;

- Re-prioritisation of the appraisal of bids to re-balance technical in relation to commercial elements;

- Resource adequately FCDO’s Procurement and Commercial Division, including its engagement with technical teams on the use of negotiated procurement processes.

(c) Increase reporting on downstream partners and sub-contractors through the implementation chain

The bifurcation of the supplier market, and the concentration of large firms receiving funding window/grant management type contracts where management control is delegated away from FCDO, also has implications for the transparency of aid implementation chains – in turn influencing FCDO’s ability to control and manage VFM in its supply chains. Despite (most) prime contractors reporting on spending to IATI, downstream reporting is poor and patchy, with very few full implementation chains visible on IATI (Tilley 2021), and the amount of ODA remaining in-country (as opposed to spent on supplier overheads in the UK) often left a mystery. Ongoing efforts by the IATI Secretariat to make IATI reporting easier for small firms come at an opportune time. We recommend:

Increased compliance requirements for lead firms to report on downstream sub-contractors expenditure and disbursement;

A reduced use of large funding window-type contracts which contribute to the opacity of downstream disbursements and expenditure.

(d) Efforts to ensure that Global South firms are able to compete for ODA-funded contracts

Despite the UK eschewing the use of formally ‘tied aid’, the OECD has found that the UK awards around 70% of contracts (by value and number) to UK-based suppliers. Combined with the pattern of consolidation and acquisition by (often US-based) large firms noted above, this reduces the participation of Global South firms in ODA delivery, excluding a significant pool of expertise and one whose overheads may be less influenced by the costs of operating out of the UK. We recommend:

The active and consultative form of management outlined in (b) above include active efforts to involve smaller expert firms from the Global South;

The proportion of total ODA spend that will remain ‘in-country’ via overheads and head office salary to be given weight as part of a commitment to transparency and localization.

References

- Brown, Trevor L, Matthew Potoski, and David Van Slyke. 2016. “Managing Complex Contracts: A Theoretical Approach.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (2): 294-308.

- ICAI. 2017. Achieving value for money through procurement: Part 1: DFID’s approach to its supplier market. In A performance review. London: Independent Commission for Aid Impact.

- ICAI. 2018. Achieving value for money through procurement Part 2: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management: A performance review. London: Independent Commission for Aid Impact.

- ICAI. 2023. UK aid under pressure: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2019 to 2023. edited by Independent Commission for Aid Impact. London: ICAI.

Taylor, O. and Gilbert, P., 2024. Mapping the ‘business of development’: the geography of UK for-profit development contractors. Finance and Space, 1(1), pp.489-493. - Tilley, A. 2021. Aid delivery chains, organization networking and the new Networked data indicator. https://www.iaticonnect.org/group/7/aid-delivery-chains-organisation-networking-and-new-networked-data-indicator

[1] Research Grant no. ES/V01269X/1. The team includes: Professor Emma Mawdsley (Cambridge), Dr Paul Gilbert (Sussex), Dr Sarah-Jane Phelan (Cambridge), Dr Jo-Anna Russon (Nottingham), Dr Jessica Sklair (QMUL), Dr Olivia Taylor (Sussex), and Dr Brendan Whitty (St. Andrews).

[2] For example, Palladium was acquired by US-based Global Infrastructure Services in 2022; WYG was acquired by US engineering firm Tetra Tech in 2019; Tetra Tech previously acquired Coffey in 2016.